It was 2017 and I had somehow been accepted into EUROFusion’s Writers for Fusion program. We were tasked with writing for a magazine and website takedown that would be shared across European research institutes and universities. My piece was unremarkable - as expected, building commercial nuclear fusion reactors is not the quickest nor cheapest way to break out a national nuclear weapons program.1

That said, I have never forgotten the story painted by another author.

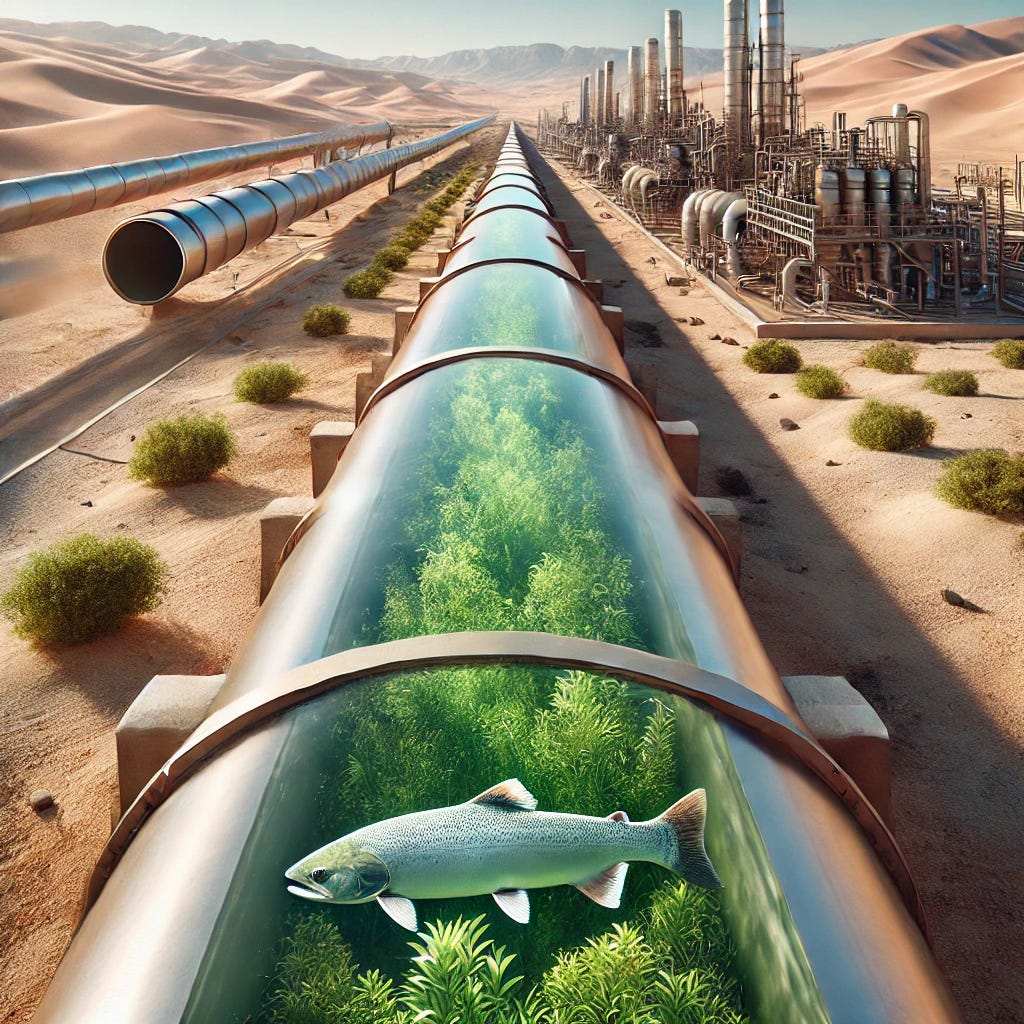

The year was 2070, commercial scale nuclear fusion was globally ubiquitous. Humanity lived in a world of limitless energy. Giant pipes were being built to channel desalinated water from the sea to the Sahara to make a garden of the desert. This was a biofuture worth a moment’s consideration.

In this essay I’ll introduce how the Biofutures content theme differs from the Verticals. Over the coming posts I’ll be bouncing between both themes along with other random bycatch.

The Great Transition

The layered combinatorial crises facing humanity this century make up a complex, multifaceted problem set. Problem sets exist in topological design spaces. This permacrisis, like those that have come before, is a biological problem to solve for. I’m calling this particular problem set The Great Transition.

We have this civilisational urge to reach for the abiotic when thinking about solves for The Great Transition.

Lab yeast can be really scary.

The deep unknowns that come with even the most well studied model organisms can frighten the hair white on well-seasoned engineers.

Organisms don’t always behave as expected, especially when convened in consortia, ecosystems and societies. There is many a banker, insurer or fund manager that struggles with financially derisking such willful microscopic homunculi. How can you possibly engineer gigatonne-scale carbon capture and storage with fickle “that’s not my medium” organisms like lab yeast?

The work of Synonym here is critical. Their Global Fermentation Capacity reports and techno-economic products deserve high praise. They plug multi-billion dollar market gaps necessary for uplifting precision fermentation capacity to attain globally and commercially relevant scales. There is obviously a verdant field here for many a consultant to make their home providing techno-economic services in the growing bioeconomy.

More than Cyanobacteria

About 2.4 billion years ago cyanobacteria triggered the Great Oxidation Event (GOE). The explosion in cyanobacteria across the oceans of the world led to a global abundance of oxygen. This one off change in geochemistry fundamentally restructured biological relations and began path dependencies to which human civilization owes its flourishing.

Humanity has now precipitated the Anthropocene and we’re beginning to push back against the GOE. We need to ask ourselves, are we more than just a one off geochemical reaction? What actually makes us different to cyanobacteria?

Another way to formulate this question is to ask, how sustainable should our circular economies be?

It’s only been 2.5 billion years since oxygen was in abundance, maybe it’s time for Earth to have a new 2.5 billion year plan.

The decisions we make set the path dependencies of what is to come. If we believe an indefinitely sustainable economy is needed for a planet with finite resources, then I’d argue we shouldn’t shortcut the dictionary definition of sustainability. The issue of the 21st century is not whether we can sustain life as we know it in a circular carbon cycle, it's whether we can accurately conceptualise sustainability at all.

This is why words matter, and why I've begun this newsletter at the highest level of abstraction available. The eons of big-time should concern us as much as the seven day weather forecast or venture capital’s five-year buy-and-hold runway. We don't measure temperature by watching the atoms dance. We simplify the overall state of the system and that simplification drives the measurement. The result may be little more than one bit of information. Suddenly a kettle of dancing atoms becomes an analogue of infinity crushed down to its singularity.

The biological boundaries of being

Part of the difficulty with setting policy for global system-level sustainability is that we2 have not evolved a fitness to think this way. This is most apparent at the nation state-level, but cascades through scales of biology all the way down to our capacity to perceive and act on long-term risk. Our expertise is local, our faculties are finite, and we are bordered by very real physical limits to our instantiated being.

This is where I will focus the Biofutures theme of this newsletter. What are the long-term scenarios we are trying to instantiate on Earth?

Through understanding methods of applied foresight, futures studies and analysing good old fashioned science fiction and fantasy, we'll explore the ways humanity might evolve civilisational fitness for long-term sustainable planning and habitation.

Delphi scans are dear to my heart, backcasting is a nice way to fall asleep at night, and expert elicitation is a fancy way to say “I talked to someone with crazy ideas”. National technology roadmaps, organisational strategy and economic forecasts — these are just tools of the trade for anticipating tomorrow. We should never stop questioning the assumptions these forecasts are built on, or the robustness and rigour of their underpinning methodologies.

I'm going to start painting scenarios for different biological futures in an effort to test your biases and assumptions. These won't be National Intelligence Council once-in-an-administration scenarios. They will be essays written as prompts to test the boundaries of what you believe could be possible. We'll take science, technology, language and culture, and measure their weight against the trends and forces at work in the world.

What would it take for all of humanity to live off cellular agriculture?

Shouldn't we upgrade our forests, kelp and cyanobacteria via horizontal gene transfer for increased carbon uptake?

Why might these scenarios privilege particular distributions of power over others? Or to put it another way, what could possibly go wrong?

A Medieval Footnote

Carbon went up, carbon went down, no nuclear weapons were used. That's the century I want to live in. Our role is to turn the 21st century into an unremarkable footnote of history.

We do this through the words we use, the economic measurements we take, the technologies we standardise, and the financial markets we make.

Over the coming months I’m going to bounce between the Verticals and Biofutures as key thematic anchors. Put simply, I'll describe the now, and the becoming. In doing so I'll try to partition useful categories of knowledge, interlinking the old with the new.

Returning to the 2070 scenario of ubiquitous nuclear fusion, if this were to manifest — and there are plenty of reasons why it might not — then the bioeconomy’s role is to get human civilization from where it is now to commercial fusion rollout, with minimal disruption. By the time nuclear fusion arrives we need those tokamaks to be little more than a supporting act for the circular bioeconomy of that era.

Biology is our pathway for solving the problems of today. Abiotic technology is not enough, it never was. This world is first and foremost a living system. Calling this newsletter Biofutures was always a conceit, there is no such thing as any other kind of future if we are to walk within it.

The Biofutures series paints scenarios with the techniques of applied foresight and the elbow grease of imagination. These scenarios are intended to push the boundaries of what you believe is possible.

All images made using DALL·E, prompts available on request.

The link to this marginally interesting piece of my early writing has long since died from the internet, the only marker I retain that the event even occurred is a picture I took when EUROFusion went to the effort of mailing a mug and a magazine to my desk in Australia.

By we I mean humans, corporations, states and other supra-national entities like the European Union or the United Nations. ‘Fitness’ is an interesting and contestable term to deploy in this context, but there are few better words for describing this problem. ‘We’ developed our ecological fitness in the age of resource abundance, and now ‘we’ are painfully coming up against some hard-edged planetary boundaries. Strangely, fortunately, even fortuitously, adapting to these planetary boundaries will be a huge source of economic growth. ‘We’ just need to figure out how to develop a fitness for thinking about growth in a more biological way.